Fruita was founded in 1884 but has an incredibly long history. Up until 1881, the area belonged to the Ute Tribe, as it was given to them during the treaties of 1868 and 1875. However, white settlers pushed them out to create another colony in the area. From that time on, the area was taken over by new residents and William E. Pabor finally gathered enough community members to create Fruita.

There are many significant historical figures that shaped Fruita into the city it is today. The orchards, rodeos, hikes and paleontology can all be attributed to people who took the time to see Fruita for what it is: a beautiful place surrounded by prosperous landscape. It was truly the people of the past and present that made Fruita a place where locals and visitors can enjoy their time and explore its rich history. Though it is almost impossible to list every significant figure, here is a list of some of the most prominent.

James Albert & Alberta Lapham

James Albert Lapham (1878-1920) and Alberta Lapham (1877-1951) were the first permanent homesteaders in Fruita in the late 1800s. There is not much known about the couple. They were traveling through the Grand Valley when they came across a log cabin that had no doors or windows and a dirt floor. They built a home out of it and added a blanket door. During their time there, they had travelers stop at the cabin for food or water. The Laphams attempted to make the area a community, but unfortunately were not able to make it a settlement. Eventually, they moved on to Utah where they spent the rest of their lives. Though the original cabin is no longer standing, the Lapham Pioneer Memorial Gazebo can still be found in Circle Park.

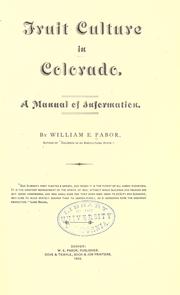

William E. Pabor

William E. Pabor (1834-1911) founded Fruita in 1884 because he saw potential in the land to grow fruit. Pabor was an author, editor, poet and founder. Born in New York, Pabor was passionate about writing, farming and horticulture and carried that with him everywhere. He was one of the founders of the CO Editorial Association, Poet Laureate of the National Editorial Association and Editor of the Colorado Farmer. He wrote “Fruit Culture in Colorado,” “Lisping Leaves,” “Colorado as an Agricultural State” and numerous poems in addition to his political career. Before coming to Fruita, Pabor was the Secretary of the Fountain Colony (later Colorado Springs) and helped found Greeley and Fort Collins.

After founding Fruita, he stayed here and continued to write and direct the formation of the city, centered around fruit. Pabor once said, “I have been in most of the fruit sections in eastern Colorado… but nowhere have I seen orchards, lands or trees superior or even equal to those in glorious Grand Valley.” In 1892, he traveled to Florida and founded the Colony of Pabor Lake, where they grew pineapples. After his health began to decline, he returned to Colorado and passed away in 1911 in Denver. Pabor Avenue was created in commemoration of the Frutia founder.

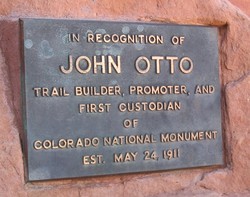

John Otto

John Otto (1870-1952) first came to the Western Slope in 1906. Soon after, he wrote “I came here last year and found these canyons, and they feel like the heart of the world to me. I’m going to stay and build trails and promote this place, because it should be a national park.” That is exactly what he did. Otto started to fundraise and lead tours around what is now the Colorado National Monument. He started to send letters to political figures like President Henry Taft. Otto was relentless and wrote Taft for years before he finally came to visit Fruita and enjoy the Palisade Peach Festival in 1909.

After the Taft visit, Otto did not hear anything back about his request to make a national monument. He continued to write and involve other citizens in writing letters until Taft signed the proclamation that established the Colorado National Monument in 1911. Otto became the Monument’s first custodian and only made $1 a month for that job. He lived alone in the canyon in a tent with a horse and burros and he built trails by hand. He named rock formations after important people and historical events in American history (though some names were added and changed). After 16 years, Otto retired and lived out the rest of his days in California. Otto’s Memorial Headstone can be found in between the Colorado National Monument Visitor’s Center and the Monument Canyon View.

Elmer Riggs

Elmer Riggs (1896-1963) started to work for the Field Columbian Museum of Chicago in the early 1900s and made many discoveries for them. Fruita is a hotspot for fossils and other natural wonders due to the many climates the area has been through in the past. However, in 1900, people believed that there were no fossils to be found in the Grand Valley and left it unsearched. That was until a farmer reached out to Riggs and provided proof of bone fragments. Riggs decided to visit the area and found many bone fragments himself, which led to him searching the entire area for more.

First, they uncovered the shoulder and foreleg of a Camarasaurus before moving spots. There, they discovered the partial skeleton of a new sauropod genus, the brachiosaurus altithorax, in 1900 on what is now known as Riggs Hill. The species was previously unknown and was the largest fossil discovered at the time. Excited about the discovery, he decided to move on to another dig site where they found the apatosaurus a few miles from the original site on Dinosaur Hill. Riggs inspired other paleontologists to comb the area and Fruita ended up with two dinosaurs named after the city: Fruitadens and the Fruitafossor. Those interested can visit Riggs Hill, Dinosaur Hill, the Dinosaur Journey Museum and walk the Fruita Paleontological Area.

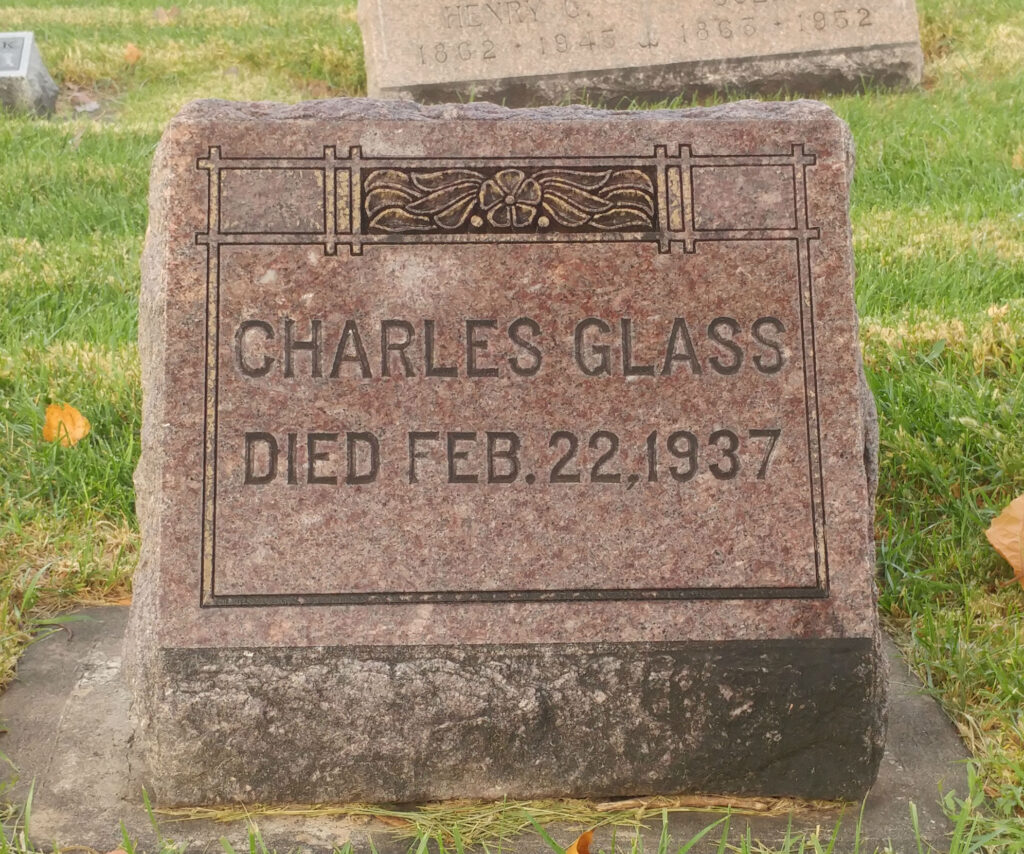

Charlie Glass

Charlie Glass (possibly 1872-1937) was considered the only Black cowboy in the West, though that wasn’t completely true. Glass was ¼ Cherokee as well and grew up on a reservation in Oklahoma. His father was accused of murder and killed, and it was rumored Glass took revenge before leaving the area and coming to the West. Though no one knows how old Glass really was, the best guess was that he was in his late 60s when he passed away. Glass was constantly visiting Fruita, though he was not allowed to hold residence in the town, to bull ride and participate in other activities. He worked across Colorado and Utah as a foreman and cattleman and could handle the toughest horses that no one else wanted to touch. Glass was a fan favorite as he was always nice to those around him and handed out money and candy to local children. There was even a ballad and a radio drama written about Glass.

“…Charlie Glass, Charlie Glass, was a cowpoke, boys, who had a lot of class. Though he’s passed the Great Divide, All the cowmen speak with pride, ‘Bout the cowpoke that they knew as Charlie Glass.” – “The Ballad of Charlie Glass” by William Leslie Clark

Glass’ story took a darker turn when he shot Felix Jesui, a sheepherder, in self-defense in 1921 for encroaching on his boss’ land. He was arrested and held for $10,000, which his boss paid, and then tried in Utah where he was fully acquitted. Glass continued to work in and around Fruita for 16 more years before retiring and gambling for fun. One night, he ran into sheepherders rumored to be Jesui’s cousins and decided to gamble with them. Eventually, they all got into a truck and drove off. Later that night, Glass was found dead in the back of their pickup truck and the sheepherders claimed they rolled off the road. There were rumors that the killing was intentional, but there was never any proof. Glass was the first Black person to be buried in Fruita’s graveyard despite it being prohibited at the time. People can still visit his headstone.